The private space sector isn’t as new as most people think. Space startups built by enterprising pioneers have existed for decades. Most people think of SpaceX as the pioneer that started it all, and it’s certainly the most successful – so far – but it’s also just one of a collection of largely unknown others that didn’t make it. Not to mention several space startups of the same era, like Virgin Galactic and Blue Origin, who are still around today. Before this there were several generations of space startups paving the way for today’s giants in the 1990s, 1980s, and earlier. Even the aerospace primes – today, effectively privatised extensions of governments who we feel have been around forever since they’re older than we are – they too were once startups founded by enterprising and quirky founders.

Space has, and always will, go through waves of progress and decline.

Whether you consider ‘New Space’ to be a period that was launched when SpaceX became the first orbital launch service to disrupt the status quo in decades, or the boom that happened around 2010 when consumer electronics – driven by smartphone electronics – changed the way we started building satellites, the key lesson is that the private sector has undergone several transformations over the years.

And it’s happening again.

For years there have been a lot of inefficiencies in the private space game. These aren’t things that we’re only learning with hindsight, most of us have been calling them out for years, but the market can often be irrational for longer than it necessarily should. This doesn’t mean I’m bearish on space, it’s my business to invest in space tech and not only do I believe there’s always opportunity in adversity, but I can also see a lot of opportunity around today.

The discrepancy comes from me having always been an outsider with a different perspective than the crowds. Let’s dive into some examples:

1. Decreasing launch prices alone aren’t going to revolutionise the space industry.

Why? Mostly because those cost savings by the launch providers aren’t being passed onto satellite operators, and the increased supply in launch is being met with increasing demand by satellite operators. Also because launch prices are still opaque and fragmented. Take Amazon’s Kuiper satellite constellation for example. Later this year they’ll launch a couple of the first satellites for its constellation for $6 million each. A future launch will cost them about $3.2 million each, another $6.1 million each, and then $4.4 million. Launching satellites is a pain, and it hasn’t really become any easier in recent times.

It’s also about to get much more difficult as launch providers – who operate in a relatively low-margin business – are starting to develop their own satellite platforms and services to try and grow further. This pressure is going to be hard for today’s satellite operators, who will still have a price premium to contend with, to match.

1/ 100% agree with Ian. We must be on the same wavelength because I was explaining the exact same thing to one of my LPs yesterday. Also.... pic.twitter.com/HT1RN33PrH

— troy 🚀 (@Troy_McCann) May 20, 2022

2. There’s too much capital in the launch business

This one has been something several of us in the industry have been calling out for years. As far back as 2018 it felt like every VC fund was investing into a launch company. When VCs race to invest like this it becomes less about fostering an innovative business model enabled by tech, and more about fuelling a highly competitive race. Most of these bets will lose. The world doesn’t need 200 launch providers, even if only half of them actually develop a successful vehicle.

It’s great to see a lot of hardware engineers inspired by SpaceX, and a lot of VCs excited to support something different to software, but we need less sheep and more enterprising, visionary leaders.

Is there a bubble in space?

I think there’s a bubble in launch and satellites. I think that we’re going to see a lot of consolidation in the satellite market as they compete for customers amongst each other as well as the launch companies who are moving downstream with cheaper access. I think we’re going to see consolidation in the launch market, where most of the lagging startups who haven’t gotten to market will run out of capital, and others will struggle to compete with the launch operators able to fuel accelerating operations with more lucrative satellite operations.

But I don’t think there’s a bubble with space, overall. In fact, I think it’s generally undervalued.

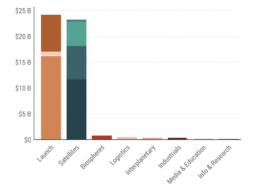

Most of the record investments into the private space industry over the past decade have gone into launch and satellites. A negligible amount has gone into truly innovative and potentially ground-breaking (?) startups.

Even putting the competition and consolidation of launch and satellites to one side, we need to realise that those domains are hardly doing anything new anymore. They’re not serving significantly different markets than they were 20 years ago – governments and telecommunications. The space industry might have been growing, but it’s hardly the revolutionary industrial boom that it could be.

It’s one thing to move atoms from A to B, but if only rocket scientists can actually use the atoms now at B then there’s not much new utility from the exercise.

Therein lies the problem. The bullish narrative for space was always one of democratisation: “we’re triggering a Cambrian explosion of opportunity, with new stakeholders using space to do new things that couldn’t be done before”.

What we’ve seen over the last decade is barely innovation, but an increased shift of activity from the government to the private sector. We’re witnessing the birth of new primes, who managed to capture a small window of opportunity to create some small gains through 3D printed rocket engines and the use of consumer electronics that surpassed the expensive rad-hard variety. But what’s next?

No one would buy a car if there were no roads to drive on. We need the utilities of space.

Clearing the way for a new industrial revolution

Call me a masochist, but I’m looking forward to today’s economic pressures clearing out some of the inefficiencies in space today. VCs are becoming increasingly conscious about unnecessarily capital-intensive opportunities, freeing up their attention to focus on other opportunities – particularly smart opportunities combining innovative tech built by great teams with a novel business model, the latter of which has been largely absent in recent years.

This is a great time to be building a business leveraging space. With the economy on shaky footing, investors know they can’t continue with the excesses of the past decade. We know that property investments can’t continue to be treated as artificially inflated treasury bonds. We know that there’s little to be gained creating different financial infrastructure in this environment, which only shifts the goal posts for a short while, traditionally benefiting early investors while doing nothing to increase the productive capacity of the economy.

With the capacity of governments and reserve banks around the globe tapped out after years of stimulus packages that ultimately failed to increase the productive output of global economies, the only way out of the mess is to industrialise.

Space is the way forward here. It can act as a domain for both economic stimulus and a relief valve for the environment, by enabling the production and manufacturing of resources beyond our biosphere, rather than needing to consume more from within it.

Troy McCann

During university, where he studied computer science and electrical engineering, Troy mixed his passions for technology and entrepreneurship through multiple engineering-heavy businesses. Using his experiences in commercialising deep research and the space industry, Troy began to develop a framework for supporting the growth of commercial solutions to humanity’s most difficult challenges while assembling a community around it, forming the basis for Moonshot.

Troy was ranked the 4th most influential new space business leader of the industry in the NewSpace People Global Ranking Report for 2019.

1 Comment

Comments are closed.

Troy, very well put. In particular, I want to reinforce the spread of activity imperative. With all that effort in launch technology and facilities, and satellite construction and operation there are huge gaps in unserved customer needs.

Capital intensity of development and operations mean that for launch providers to thrive they need excess demand for their services for decades!!

If they vertically integrate in an effort to capture more revenue streams and subsidise their core operations then they face the higher risks of failure that come from greatly exaggerated complexity. We see this in the way the automotive manufacturers operate within a multi-tiered industry structure that offers each company the chance to have multiple suppliers and multiple customers. The impact of competition and choice on supply costs and market access are essential to maintain economic efficiency. Even more exciting though is that this form of competition drives innovation forward, at least until the industry reaches the cartel stage which effectively squashes innovation in favour of monopoly profits.

Launch consolidation will happen but, that does not mean only a handful of survivors. What we are seeing is that launch will segment itself by type and scale of payload, as well as by geography and political barriers to access. National pride will play a role as will competing engine and re-use designs.

Another analogy for launch is the telco. Originally, primarily an infrastructure provider for a single service used by everybody, telcos have had to evolve so now there are telcos that have no infrastructure of their own and they all offer an increasingly diverse range of services.

Similar futures are likely to play out for satellites, although that is already a more complex market segment where even high school students can build a viable satellite. So the satellite space faces some other challenges, e.g. do we really want 100,000s of satellites of all types and sizes circling the Earth!?!?

Are we giving enough forethought to the environmental impact of space, particularly biosphere impact for launch and orbital impact for satellites??

If we manufacture in space, how do we ensure that the manufacturers don’t pollute the orbit the same way early manufacturers on Earth polluted ht air and the waterways??

After all, a stray screw colliding with a satellite or habitat at orbital speeds could be enough to create a disaster. How much more concerning would be a cloud of debris from irresponsible in-space manufacturers.

My point is about learning from the past to build a better future but, it is also about recognising that every one of these questions creates opportunity for remarkable innovation and prosperity generated by the companies that solve these challenges.